Matador said:

I believe I said 'deficit had tripled by 1990', not revenues declined in 1990.

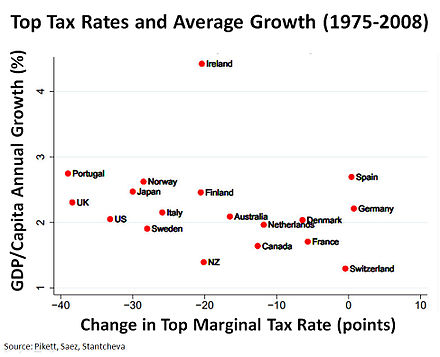

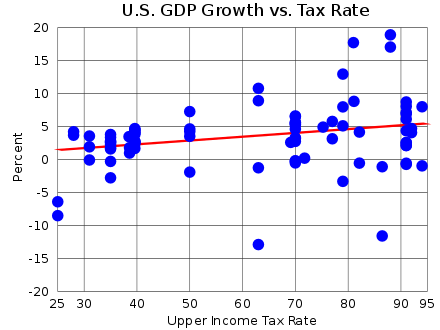

I will agree causation is a pain, especially in complex systems like the climate and large-scale economies. However trickle-down is sold under the brand name of "Lower taxes and everyone will prosper", which hasn't been proven to be the case in any measurable sense since it was attempted back in the 1980's. In fact, there is a strong correlation between government investment in infrastructure / public works and long term economic benefits. One need only look to the New Deal and the post WW2 expansion to see evidence of this, even during periods of relatively 'high taxation'.

To return to the New Deal, one might consider this to be the economic version of quantum supersymmetry, which is exactly opposite in sign and magnitude from trickle-down. This would theorize that an expansion in public works, spending, and taxes, might have the effect of boosting the low-term economic growth of the country, just as it did in the 1930's and 1950's. I still find it strange that people still cling to "less taxes = growth", despite it never having being proven to work long term, and immediately dismiss "more taxes = growth", despite three decades where it was highly correlated with long-term growth.

I can't agree with the causation of growth in a post-WWII era being because of high taxes. There are so many confounding effects there, not the least of which being the only major world economy not decimated by the war. I think we can easily imagine that there is an optimum amount of infrastructure and public spending, and that it is somewhere north of 0% and somewhere south of 100%. Likewise taxation.

The fact of the matter is, the New Deal policies were not successful at pulling the US out of the depression. Whatever we may think of them politically, the GDP growth numbers are objective.

While the economy had somewhat recovered, it was far too weak for the New Deal policies to be unequivocally deemed successful. In 1933, at the low point of the contraction, GDP was 39% below the trend before the stock market crash of 1929, and by 1939, it was still 27% below that trend. Likewise, the number of private hours worked was 27% below trend in 1933 and was still 21% below the trend in 1939. Indeed, the unemployment rate in 1939 was still at 19% and would remain above pre-Depression levels until 1943.

https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/011116/economic-effects-new-deal.asp

I think here we simply have a fundamental disagreement. Capitalism, the wisdom of crowds and markets, is demonstrably superior to command economies. Whats more, on an ethical or philosophical level, people should be free to spend their own money as they see fit; every dollar spent by the public corporately is one dollar less spent by individuals in aggregate individual capacity. Just on principle, I think that the combination of the moral hazard and the known efficiencies of markets strongly outweigh any perceived advantages of increased central planning. Where to draw the line is always the question, though.

One could imagine a theoretical multi-trillion dollar investment in energy infrastructure, to eliminate (or greatly reduce) our dependence on foreign entities for energy demands: what a transformative effect it could have on the populace, from reduced energy costs, changes in foreign policy, reduced support for bad actors in the Middle East, and potentially a large impact on damage to the environment (if done properly).

So, I do business strategy for a living for a multinational company -- this is an area I can speak coherently and with some fair amount of confidence on. What you're advocating for is absolutely, positively, without a doubt inefficient...and based on some bad presuppositions.

For starters, we are more or less independent from foreign entities for energy demands. The shale gas revolution has made cheap natural gas a guarantee for the foreseeable future. The US has the capacity to build as many nuclear plants as we like. We do not need the USG to inefficiently (by comparison to the market) central-plan monetary spend to foster energy independence. Even a clean one.

Subsidies into the power market are absolutely wrecking the industry. Renewables are not "firm" - you can't dispatch them and they're inverter based - and come with an increased transmission cost due to the need to have dispatchable firming, backup power, conditioning, and the simple need to move the power from where the wind or sun is to where it is needed. What's more, they're unnecessary. Wind and solar prices have been decreasing - solar at exponential rates - for decades. The market isn't stupid; when the levelized cost of electricity for renewables is lower than traditional generation, the market absolutely will switch over. We know because this is happening. Subsidies only make this entire picture unclear, and at some point they can even hinder adoption because of the unknown duration of the subsidy creating a difficulty to forecast and therefore finance the viability of these large capital projects. Even further, because of the secondary and tertiary costs associated with a heavy renewables mix, forcing adoption ahead of viability can have some severe unintended consequences - grid instability, actual increased electricity prices, insufficient backups driven off the grid, and so on.

Tell your friends: renewables will continue to grow. Solar is legit. The future is bright! We'll still need thermal or nuclear power for the foreseeable future because of the need for terawatt hour level storage for seasonal demands, but 100 megawatt hour level storage is a reality today. This is awesome and really cool.

We don't need the USG to tax us and then give the money back as infrastructure spending for this to happen. It will happen because the technology will eventually simply be superior. Just like we transitioned from horses to cars, or motorola razrs to iphones -- or, in direct comparison, from coal fired power to gas turbine generators. The market will use the best technology available, and that's really great.

![Electronics Soldering Iron Kit, [Upgraded] Soldering Iron 110V 90W LCD Digital Portable Soldering Kit 180-480℃(356-896℉), Welding Tool with ON/OFF Switch, Auto-sleep, Thermostatic Design](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41gRDnlyfJS._SL500_.jpg)