Lerok

Active member

Hi, I've been floating around the forum recently, researching projects, etc, and one thing that I'm still struggling to get my head around is impedance, and specifically how it manifests in older schematics (such as the Helios/Neve/Trident 3 transistor amps).

So, I think I have a fair understanding of impedance when it comes to modern amplifiers, but I want to sort of get it on paper and ask some more knowledgeable people to really verify that I'm not being an idiot

My (very crude) impression is that input impedance is typically determined by the resistors used at Audio frequencies (assuming a solid design) and capacitors have minimal impact. I'm also aware that modern opamps have extremely high input resistance, and theoretically 0 output impedance (which can be modified by affixing a resistor to the output, as seen in most IC preamp designs). So here are my questions:

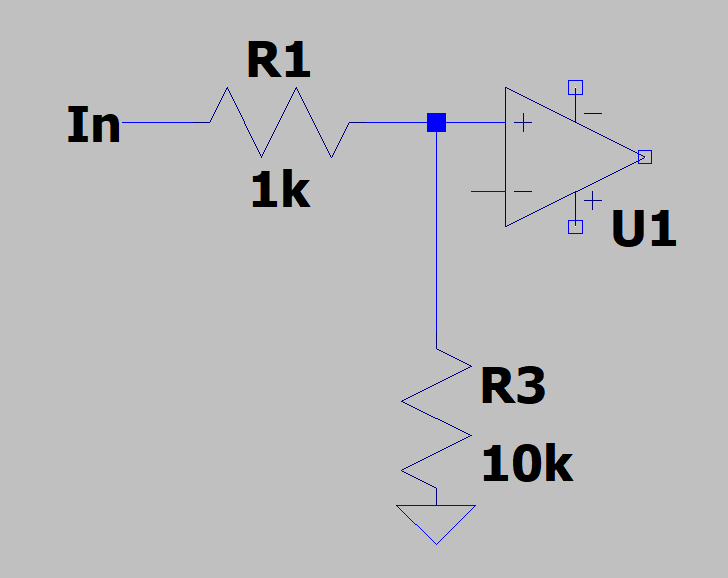

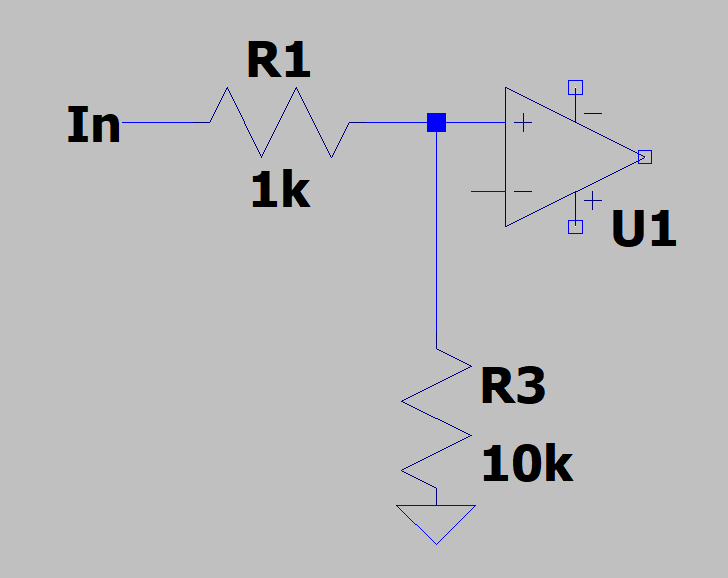

1. Assuming that this opamp is ideal (infinite ohms on input, 0 on output), why does the impedance not compound? With resistance, putting say two 1k resistors in series creates 2k worth of resistance - given the infinite impedance of the opamp, why is the impedance of this circuit not infinity + 1k?

2. Is impedance affected by only components in the signal path, or would the impedance of this be somewhere around 11k due to the 10k shunt to ground? I know it's a super basic question haha.

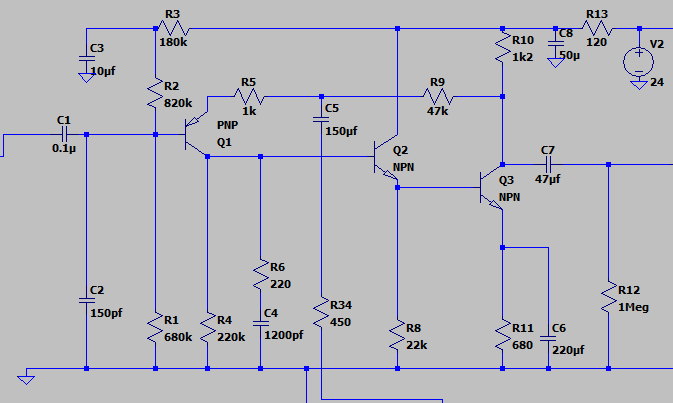

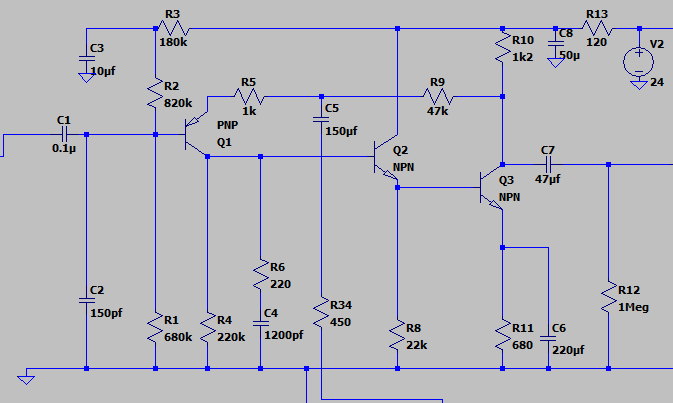

And finally 3, which is a bit more general: what determines the amount of impedance that can be driven by a given schematic? For example, I'm aware that something like the helios preamp below will struggle to drive a 600 ohm transformer, and there is an additional stage added to make that possible. Is this a function of the current in the circuit not being enough to push a load into the transformer?

Sorry for such basic questions, I'm very much a hands on learner and while my experimenting with audio circuits has gone swimmingly so far, I don't want to get ahead of myself, and figure clearing up some confusion on key topics is a good thing to do

Thanks! Ronan

So, I think I have a fair understanding of impedance when it comes to modern amplifiers, but I want to sort of get it on paper and ask some more knowledgeable people to really verify that I'm not being an idiot

My (very crude) impression is that input impedance is typically determined by the resistors used at Audio frequencies (assuming a solid design) and capacitors have minimal impact. I'm also aware that modern opamps have extremely high input resistance, and theoretically 0 output impedance (which can be modified by affixing a resistor to the output, as seen in most IC preamp designs). So here are my questions:

1. Assuming that this opamp is ideal (infinite ohms on input, 0 on output), why does the impedance not compound? With resistance, putting say two 1k resistors in series creates 2k worth of resistance - given the infinite impedance of the opamp, why is the impedance of this circuit not infinity + 1k?

2. Is impedance affected by only components in the signal path, or would the impedance of this be somewhere around 11k due to the 10k shunt to ground? I know it's a super basic question haha.

And finally 3, which is a bit more general: what determines the amount of impedance that can be driven by a given schematic? For example, I'm aware that something like the helios preamp below will struggle to drive a 600 ohm transformer, and there is an additional stage added to make that possible. Is this a function of the current in the circuit not being enough to push a load into the transformer?

Sorry for such basic questions, I'm very much a hands on learner and while my experimenting with audio circuits has gone swimmingly so far, I don't want to get ahead of myself, and figure clearing up some confusion on key topics is a good thing to do

Thanks! Ronan

![Electronics Soldering Iron Kit, [Upgraded] Soldering Iron 110V 90W LCD Digital Portable Soldering Kit 180-480℃(356-896℉), Welding Tool with ON/OFF Switch, Auto-sleep, Thermostatic Design](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41gRDnlyfJS._SL500_.jpg)